By definition, learning cannot be outsourced

Thoughts on AI and Education

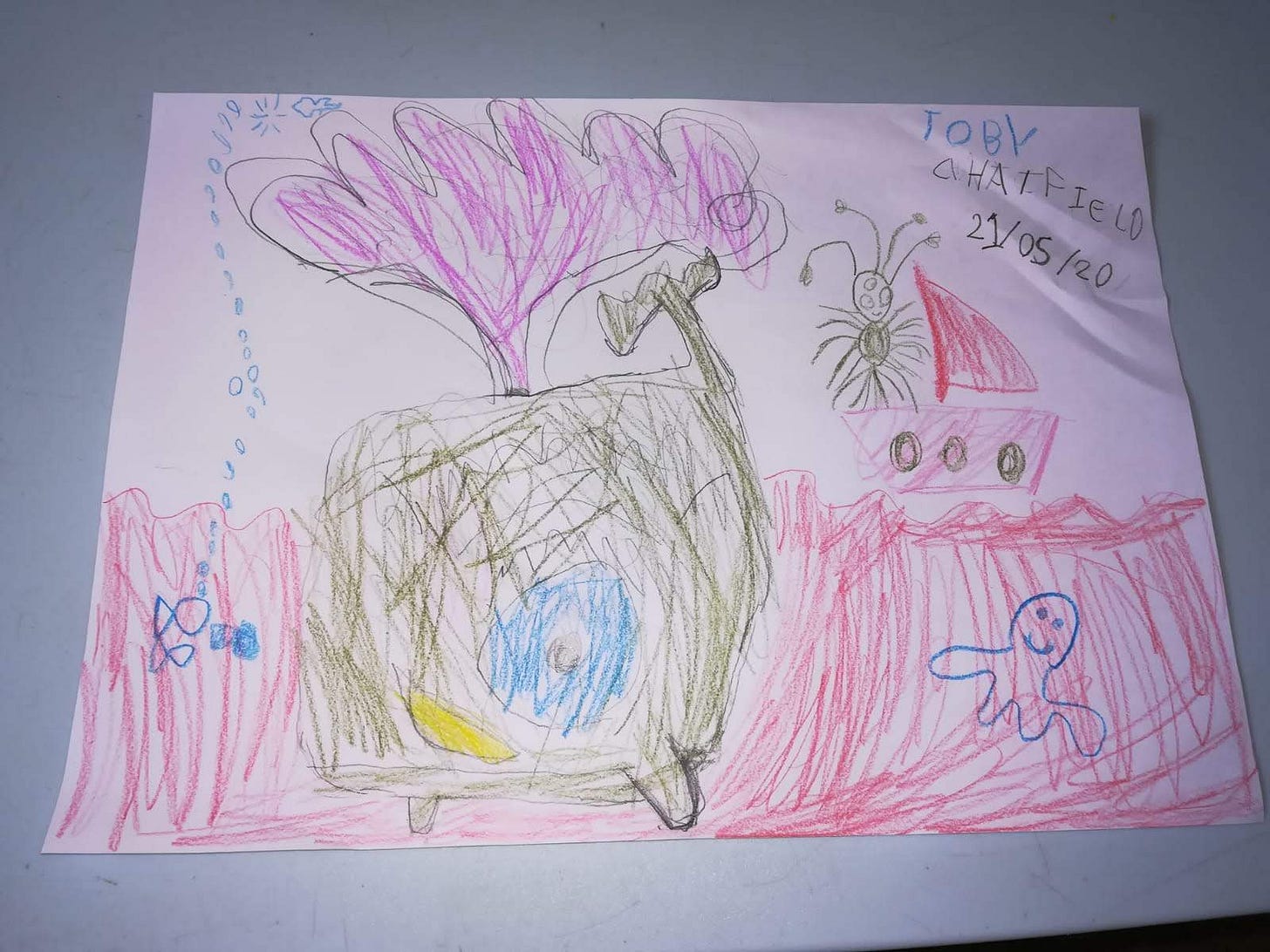

An Old Master from our kitchen wall: don’t automate this.

Over the last six months, I’ve been writing and researching a white paper for Sage publishing, alongside co-developing a prototype LLM “cognitive co-pilot” that aims to teach critical thinking and AI literacy skills (as you do).

It has been fascinating, hard and thrilling, not least because working with AI allows you rapidly to turn ideas and resources into testable, playable prototypes; and then to wrestle with the strange mix of hyper-competence and fragility that accompanies this.

The paper can be read in full here and, given how crowded the space around it is with hype, doom and genuinely illuminating commentary, I’m delighted that it seems to have struck a chord with some educators in its first few days—perhaps because I’m more interested in wrestling with tricky tensions, and testing different possibilities, than I am in coming up with a Grand Solution™.

Rather than regale you with a synopsis, I’ve reproduced my Introduction to the paper below. Do read further if you’re interested; do share and join the conversation.

This paper explores how education can respond wisely and imaginatively to the rise of AI in general, and generative AI in particular. Its recommendations are rooted in two principles.

1. Innovation must draw on what we know about how humans learn.

2. AI’s power must not be allowed to hollow out the very skills required to navigate an AI age successfully.

The tension at the heart of this second point bears spelling out. Within the space of a few years, it has become possible to simulate knowledge and understanding of almost any topic while possessing neither. Freely available tools can be used to complete conventional assignments and assessments with ease, in the process potentially preventing students from gaining the very skills required to use AI adeptly: critical discernment, domain expertise, research and verification, analytical reasoning.

Already, the use of AI by students is almost ubiquitous. In a December 2024 survey, 92 per cent of British undergraduates reported using AI tools. As the author and Washington University professor Ian Bogost noted in August 2025:

The technology is no longer just a curiosity or a way to cheat; it is a habit, as ubiquitous on campus as eating processed foods or scrolling social media.

From creating study guides to explaining key concepts, from constructing quizzes to proofreading essays (not to mention grading papers and drafting student feedback), AI is being used across the entire spectrum of educational activities. Yet much of this usage exists in a shadowy zone of mistrust and ambiguity. Both students and instructors have at their disposal a seductively potent tool that is upending the practices and the principles of 21st century education.

The greatest risks, here, are bound up with the unique nature of learning. By definition, learning cannot be automated or outsourced. To learn is to acquire knowledge and understanding via the meaningful exercise of a range of skills. As the author Nicholas Carr put it in May 2025, “to automate learning is to subvert learning.” When children at a primary school write stories and draw pictures, the point is not to supply the world with a stream of winsome content. It is to help them become literate, reflective participants in their society. Undergraduates do not write essays or conduct experiments because the world needs more such things. The process is the purpose.

This is not to deplore technology. When used well, technologies like generative AI can facilitate rich and potentially transformative forms of learning; while the reflective and critically discerning use of information systems is a fundamental modern literacy. But saying this only begs the question. What does it mean to introduce novel forms of automation into education wisely? How can the demoralizing or corrosive effects of misuse and abuse be mitigated? This paper addresses these questions across four sections:

1. What works in Education? Faced by fresh threats and opportunities, it is vital to dig into human fundamentals and to ground innovation in best practices around the essential purposes and processes of learning.

2. Leveraging Technology for Excellence. The history of technology in education long predates artificial intelligence. Emerging insights need to be combined with larger lessons about what has and has not worked before (and why).

3. Beyond the Arms Race. Many established forms of assessment are in crisis, with AI fueling distrust and conflict between learners, instructors and institutions. In the long term, everyone loses if education becomes an arms race.

4. Raising the Cognitive Bar. The ultimate prize of any educational technology is that it raises the bar of human insight and achievement. This section explores how AI can deepen both understanding and engagement, and what the educator and learner of the future might look like.

Ultimately, as the psychologist and philosopher Alison Gopnik has argued, it is a dangerous category error to treat artificial intelligence as either miraculous or unprecedented. Rather, it is the latest in a long line of cultural and social technologies that includes “writing, print, libraries, the Internet, and even language itself”: ways of making information gathered or created by other human beings useful in new contexts.

Similarly, no matter how powerful AI systems become, they will only ever be part of a learning process: components within a larger system whose ultimate measures of failure or success remain wholly human. Drawing on long-standing research and new forms of practice, this paper thus argues for education systems that treat AI not as a shortcut but as a context and catalyst for deeper learning; and for educators to play a central role in shaping such a future.

Fascinating! What if the LLM evolved alongside us?

The new white paper is splendid, Tom.