On staying amazed

How to remain shocked by the world

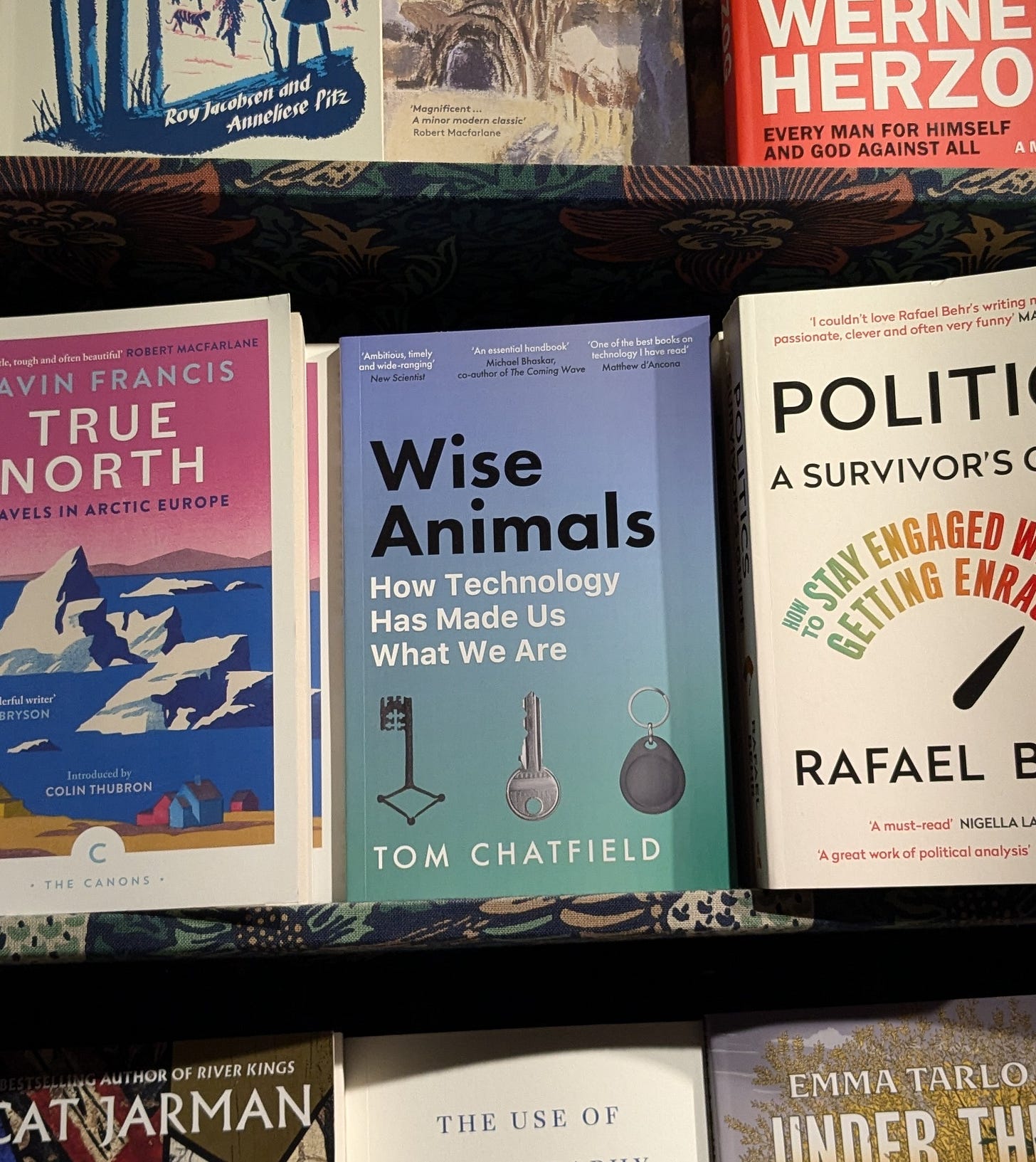

Above: thank you, Daunt Books Marylebone

My most recent book, Wise Animals, is published in paperback in the UK today. Hooray! If you’re considering buying a copy, please feel free to do so. If you’ve already read and enjoyed it, do help spread the word. And if neither of the above applies to you—well, I hope you enjoy this newsletter.

I’ve reproduced, below, a lightly edited version of one of my recent columns for the New Philosopher, exploring the idea of novelty. It’s about the ease with which novelty subsides into familiarity, and the wonder of this fact. Individually and collectively, we have an *astonishing* capacity for self-reinvention. This is one of the great themes of Wise Animals: the brilliance and burden of our plasticity; the importance of noticing just how unlikely, terrible and marvellous is our human-made world.

It's a breezy crisp afternoon in San Francisco. A white car with a spinning dark scanner set into its roof turns across the street in front of me. I stop and stare before fully realizing why I’ve done so: neither a driver nor passengers are sat inside. Smoothly, the steering wheel turns of its own accord.

This isn't yet a familiar site, but it will become one. Two hundred years ago this land was woodland and scrub. Signposts memorialize the rise and fall of industries, neighborhoods, ways of life. Now driverless cars whine peaceably past billboards boasting that Anthropic’s Claude, one of a handful of cutting edge Large Language Models, is “a jetpack for your thoughts.” This is presumably a reference to the effortless ease of science fiction rather than the alarming reality of strapping miniature jet engines to your body. Although the passion with which novelty is applauded in this city makes me wonder.

I'm here to speak about Artificial Intelligence, a phrase I distrust because it claims and presumes so much. Systems like Claude are formidably adept at extracting statistical insights from vast amounts of data. But yoking humans and machines together as analogous forms of “intelligence” doesn’t, I think, help us understand what’s happening on either side. The wonder of AI is precisely the inhuman means through which its insights are achieved, far beyond biological scales and speeds.

For the author, cognitive scientist and AI pioneer Douglas Hofstader, the philosophical lessons that follow from this are profound and alarming. As he put it in a 2023 interview:

Maybe the human mind is not so mysterious and complex and impenetrably complex as I imagined it was when I was writing Gödel, Escher, Bach … It makes me feel, in some sense, like a very imperfect, flawed structure compared with these computational systems that have a million times or a billion times more knowledge than I have and are a billion times faster. It makes me feel extremely inferior.

Hofstader’s concerns are of a piece with what Freud termed the “existential insults” suffered by humanity in the face of technological and scientific advances. Once upon a time, we believed the Earth to be the centre of the universe. Humanity bestrode a planet suffused with divine purpose. The existence of a spiritual realm, underwriting earthly ethics, was as self-evident as our own special status.

Then, across a few centuries, we learned new and startling things. Telescopes showed distant moons orbiting other planets, then distant stars and galaxies scattered through an immeasurably vast cosmos. Beneath our feet we found billions of years of sunken history, complete with vanished species and incremental transitions. Freud’s work hollowed out the prospect of reasoned self-knowledge; while the rise of computation gradually gave the lie to our uniqueness as rational organisms.

Amidst all this, philosophy’s great questions can seem comfortingly ancient. What does it mean to be human? How can we live and die well; seek purpose and beauty; sift truth from falsehood? Yet this seeming continuity conceals epochal changes. The very meaning of words like “human,” “purpose,” “truth” and “consciousness” has shifted profoundly over time. Looking back via neat synopses and handy translations risks erasing history’s strangeness and difference.

To be a citizen of the 21st century is to be born into a vast inheritance of knowledge, scope and struggle. As the psychologist and philosopher Alison Gopnik argues in her 1998 book The Philosophical Baby, humans are unique in inhabiting an environment that is primarily the product of our imaginations; that is the child of countless minds:

If I look around at the ordinary things in front of me—the electric lamp, the right-angle-constructed table, the brightly glazed symmetrical ceramic cup, the glowing computer screen—almost nothing resembles anything I would have seen in the Pleistocene. All of these objects were once imaginary—they are things that human beings themselves have created. And I myself, a woman cognitive scientist writing about the philosophy of children, could not have existed in the Pleistocene either. I am also a creation of the human imagination, and so are you.

The further we move through history, the larger the human imagination and its works loom; and the more our minds are interwoven with artefacts embodying numberless legacies, experiments and iterations. This is one of the most obvious ways technological modernity can be said to alienate us from both other creatures and our own origins. At the same time, however, these ancestors remain right beside us in the newness of each child: in their adaptivity and fierce desire to learn; their deep interest in other minds; their playfulness and lack of presumption.

“More than any other creature,” Gopnik writes, “human beings are able to change. We change the world around us, other people, and ourselves.” Novelty is both our birthright and our supreme survival strategy. In this context, Anthropic’s jetpack analogy is revealing. People cannot fly, move at five hundred miles an hour, recall a trillion bytes of information or exchange ideas instantaneously between continents. Yet technological civilization facilitates these and countless other miracles. The unit of agency that matters isn’t the unaided individual. It’s humanity itself, enveloped and enhanced by all that we have brought into being.

Like Hofstader, I am awed and discomforted by what technologies like AI may accomplish and signify. But I am also deeply uncertain. From day to day, I shift between elation and fear, hope and cynicism. And the thing that worries me most of all is the flip side of our appetite for novelty: how soon the shock of the new subsides into normality; how easily we confuse whatever order we’re born into with the underlying nature of things.

In this sense at least, the great purpose (if not the tools) of philosophy remains one Socrates set 2,500 years ago: to banish complacency; to insist on wondering at the strangeness of our self-invention.

Or as my 94 year old mother said shortly before she died: "These days everything is so amazing that nothing is amazing."

This.

"And the thing that worries me most of all is the flip side of our appetite for novelty: how soon the shock of the new subsides into normality; how easily we confuse whatever order we’re born into with the underlying nature of things.

In this sense at least, the great purpose (if not the tools) of philosophy remains one Socrates set 2,500 years ago: to banish complacency; to insist on wondering at the strangeness of our self-invention."